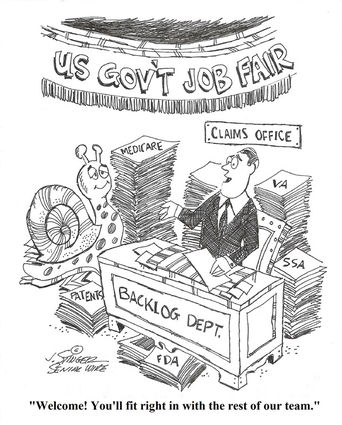

Huge backlog result of broken Social Security bureaucracy

Washington Watch

Last spring the nation was outraged when the enormous backlog of claims at the Veterans Administration was revealed. The number of claims stuck in processing for more than 125 days at that time was 611,000 veterans who were not getting their claims processed. Seven months later, that number, the VA says now, has dropped to 344,000 claims that are still 125 days behind.

While there was bipartisan anger over the VA scandal, a recent Washington Post story reveals a dramatically worse backlog over disability claims at the Social Security Administration (SSA). The Social Security office of judges, who hear appeals for disability benefits, are 990,399 cases behind. And all of these people are waiting on a single office to get help.

Social Security is best known for sending benefits to seniors. But it also pays out disability benefits to people who can't work because of physical or mental ailments. It also runs an enormous decision-making bureaucracy to figure out who is truly disabled and who is trying to game the system. The backlog is at the office that handles appeals of appeals. In most cases, the applicants have already been turned down twice by lower-level officials who didn't think the person was disabled enough.

If people appeal to this office, they can plead their case in person before a special kind of Social Security judge, who is supposed to read the case history and ask questions. There are 1,445 of these judges, which means this in-house legal system is actually larger than the entire federal court system – district and appeals courts and the U.S. Supreme Court put together.

In its recent package of stories, Washington Post reporter David Fahrenthold noted that these judges fell behind when Gerald Ford was president in the 1970s and they never caught back up. Admittedly it is slow, tedious work, made slower by outdated rules and what the newspaper called "oddball procedures," including an official list of jobs that people qualify for, that includes "telegram messenger" and "horse-and-wagon driver," from a bygone era.

The problem is that the system is, in effect, what the Washington Post labeled as "too big to fix." Efforts at reforms were hugely expensive and so logistically complicated that they often stalled, unfinished.

"What's left now is an office that costs taxpayers billions and still forces applicants to wait more than a year – often, without a paycheck – before delivering an answer about their benefits," the newspaper reported. Fighting this system is frustrating, not only for those filing, but for the judges too. One Miami-based Social Security judge noted that she had two claimants on her docket that died waiting for a hearing.

The backlog problem is not unique to the SSA. Other government agencies have the same problem. According to the Washington Post, the average case at the Social Security appeals office usually takes 422 days to decide, while an appeal at the VA will take 957 days. At the patent office, an application usually waits more than 800 days for a decision.

But what makes this Social Security backlog especially difficult is that most disability applicants have little or no income while they wait. SSA officials told the newspaper that the backlog is mainly caused by factors they cannot control. A surge of new disability applications is a key factor. The judges' incoming caseload grew from almost 600,000 in 2008 to over 800,000 in fiscal 2014. Social Security officials also say Congress has sent them hundreds of millions of dollars less than they asked for in funding.

Both Congress and the SSA have tried to speed up the appeals process by pushing the judges to work faster. But even that barely makes a dent in the backlog. Lawmakers and SSA officials have also tried to impose system-wide reforms, but they often fizzled because of the logistics of changing something so big. The switch from paper to electronic hearings and the expansion of hearings by video link have helped, dropping the backlog to 705,000 in 2010. The wait time dropped too, eventually falling below a year. But then a problem appeared.

Judges realized that it was simply easier to just say yes to appeals cases and faster than saying no. So suddenly there was a sharp increase in the number of appeals cases that the judges granted disability payments to.

After some careful consideration, Social Security officials backed off the push to get faster decisions, and judges were given a case limit of 720 a year. New checks were also imposed to makes sure the Yes decisions were as thorough as the No decisions. Today, judges approve 44 percent of cases, a marked decline from recent years. Dozens more judges have also been hired to scale back the problem. But a huge backlog still remains.