Totem poles educate millions in Louisiana during 1904 expo

Aunt Phil's Trunk

National Park Service

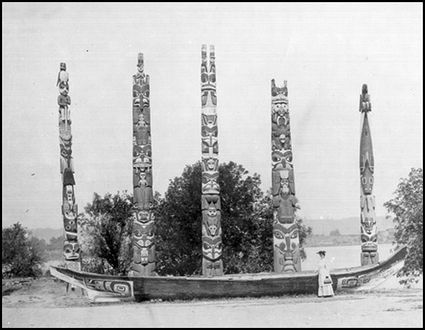

Chief Saanaheit from the Kaigani Haida village of Kasaan on Prince of Wales Island donated these totem poles and a canoe to Gov. John Brady for a display at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis.

When John Green Brady, governor of the District of Alaska, was asked to create an exhibit to publicize the Great Land for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis in 1904, he decided to showcase one of Southeast Alaska's most recognizable features: totem poles.

Brady thought a display of poles carved by Alaska's Native people would draw crowds to the exhibit where they then could learn about the real Alaska – not an icebox, but a land that offered much for tourism, settlement and development.

The governor sailed to Tlingit and Haida villages between 1903-1904 and asked leaders along the way to donate poles and other cultural objects for the exposition. Several decided to trust Brady and chose to share their heritage with the world.

Fifteen totem poles, two dismantled Haida houses and a canoe from villages like Old Kasaan, Howkan, Koianglas, Sukkwan, Tuxekan, Tongass, Klinkwan and Klawok were delivered to the St. Louis fairgrounds. A crew of Native carvers accompanied the poles in case some of the pieces needed repair.

When the Louisiana Purchase Exposition opened that April, Alaska Native totem poles helped tell close to 19 million visitors about Alaska's past, heritage and resources. Exhibits filled with technological marvels like electric lighting, the wireless telegraph and newfangled automobiles also showed visitors the future.

When the exposition closed that December, the Alaska exhibit traveled to the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland in 1905. There the poles and canoe stood along the shores of a manmade lake on the fairgrounds from June until October.

The poles then began their long journey home. They arrived in Sitka in January 1906 and were repaired by skilled local carvers before going to their final home – the first totem pole park in Alaska.

Photographer E.W. Merrill designed the alignment of the poles. Prisoners from the local jail contributed the labor to get the poles in place. By March, Brady's vision for a totem park in Sitka came to fruition.

However, the totem tradition in other parts of Southeast Alaska almost died out a few years later. Some missionaries visiting several Native villages mistakenly assumed that these poles were pagan symbols. They did not know that Alaska's First People carved the poles as a way to share the stories of their ancestors, their history and their culture. They did not know that the carved figures stacked on the totems each had a specific significance that helped tell family and clan histories, major events, achievements, deaths and more.

Zealous missionaries persuaded the people of Kake to cut down and burn their totems in 1926. Other villages lost their totems, as well. But a decade later, U.S. Forest Service and workers in the Civilian Conservation Corp found a few forgotten totems in villages along the waterways of Southeastern Alaska. They knew the totems had to be saved.

They organized a totem roundup, and using CCC funds, paid for more than 200 Native carvers and laborers to restore and replicate the poles. Some poles were so badly damaged that they had to be recreated from memory.

This effort proved successful. Many totems were brought back to their former glory.

It took another 40 years, but Kake also brought its totem culture back when, on Oct. 1 1971, it raised what was proclaimed to be "The World's Tallest Totem Pole."

Carved in 1967 to honor the Alaska centennial purchase, the raising of the pole in Kake was an attempt to symbolically rectify the burning of Kake totems in 1926. And although it is not the tallest in the world (it is the third tallest), the totem still stands in Kake at 137.5 feet tall.

This column features stories from late Alaska historian Phyllis Downing Carlson and her niece, Laurel Downing Bill. Many of these stories fill the pages of "Aunt Phil's Trunk," a five-book Alaska history series that is available at bookstores and gift shops throughout Alaska, as well as online at http://www.auntphilstrunk.com and Amazon.com in both print and eBooks.